The British Library's new fantasy exhibition opened my eyes to how important fantasy is

Lord of the things.

This might sound strange but I always worry about seeing things I love in the spotlight, because I worry they won't be taken seriously and all the feelings I have for them will be undermined. I don't like exposing a vulnerable side of myself to potential ridicule, basically. I've had enough of that from the "oh that's unusual" remarks people have made about my job over the years. So I worried, visiting the new fantasy exhibition at the British Library - Fantasy: Realms of the Imagination it's called - about how fantasy would come across.

I love fantasy, you see. I've loved it ever since I was little and I read a story about a boy who discovered a city at the bottom of a lake. He'd been hearing it call to him in his sleep or something, and one day he dived and found it. And people were living there! Everything about this took me by surprise. I didn't know books could do that, veer off from reality like that. I can almost feel my mind stretching to take it all in still. And that book, it fired something within me that remained ever since.

But fantasy has always been a relatively private thing for me, because growing up, I didn't really know anyone else who was into it. My family wasn't. OK, granted, I had my dad's Hobbit book and his The Lord of the Rings, but I'd never seen him go anywhere near them, nor near any other kind of fantasy. He read biographies. And my friends weren't into fantasy, despite my best efforts. Even when I joined Eurogamer many years ago, there was no one interested in it, though that's changed now. So I learnt to keep it to myself. I kept it secret, kept it safe.

Given that, I didn't expect to see many people at this fantasy exhibition, because I didn't think that many people were into it. And I know how ridiculous that sounds - I know there are some humongous fantasy licences you don't even have to have read a book to enjoy today. I also didn't think fantasy was something serious enough to have in the British Library, because it's got elves and goblins and magic and dragons in it. It's the silly stories Bertie likes. Who's going to see a silly thing like that?'

Imagine my face when I walk into the exhibition, then, and there are many other people there. It's really popular. And it's not just people like me: there are younger people, older people, Black people, white people, and they're all peering into perspex cases very seriously like they would at a proper exhibition about proper things. And that's when the first wave of realisation hits me: this is a proper exhibition about a proper thing. I wobble.

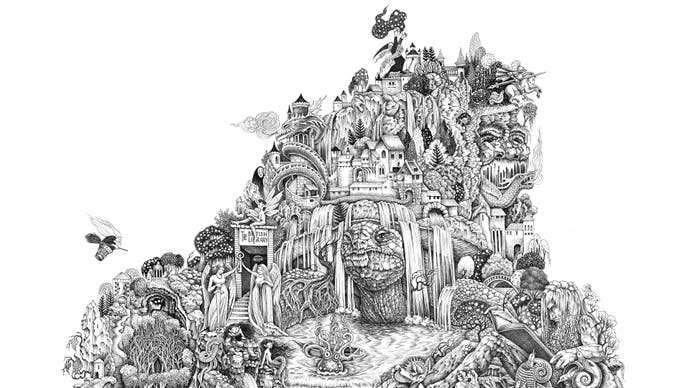

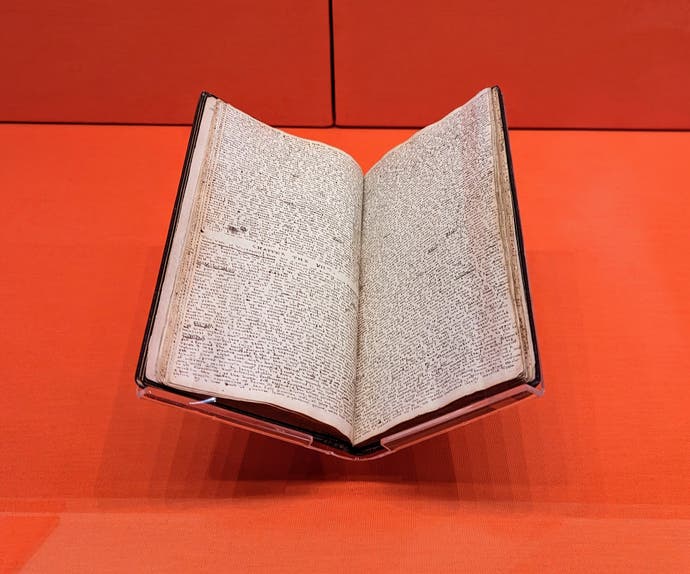

The second wave of realisation comes when I start combing through the exhibits. The exhibition is broken up into a few sections ordered by fantasy types. You'll experience them in this order: Fairy and Folk Tales, Epics and Quests, Weird and Uncanny, and Portals and Worlds. And what strikes me first about Fairy and Folk Tales are the dates I see. There's a wonderful table-length Ancient Mappe of Fairyland that greets you as you go in, that Bernard Sleigh drew in 1918, which is a pretty long time ago now. But we jump back another hundred years with Percy Bysshe Shelley's Queen Mab nearby, and then a few hundred years more with Reverend Robert Kirk's The Secret Commonwealth. Kirk wrote that in the 17th century. It's a book where he recorded his parishioners' beliefs about fairies, which is a great idea - I'd never heard of it. Around the corner, there's even a crumbling 14th century edition of Homer's Iliad.

But it's not the ancientness I find as impressive as the realisation fantasy has been desired by societies for hundreds of years. Because where there are books - particularly books that have gained the fame these have, warranting their preservation - there was clearly a demand to read them. So It's not just me and it's not just now - people have been into fantasy forever.

Actually it probably has been around forever if you consider The Iliad, or, if you really want to go back, The Epic of Gilgamesh (I've always thought it was a bit pompous calling your own story an "epic", though). These things are thousands of years old. If you think about storytelling as an oral tradition before that, and the kind of stories associated with belief systems and folk tales - which people have been handing down from generation to generation - it might even stretch back to the beginning of humanity. And that's really exciting. It means not only is fantasy entwined with humanity, and the shape of it, but also that we're not likely to get bored of it or run out of stories to tell. Perfect!

But why - what is it about fantasy we keep turning to? Well, I have a few theories of my own. One, it's quite exciting and it's nice to escape to a fantasy world. But also, and herein maybe lies the real reason, it provides us with a safer place to explore more challenging themes from our real lives. It's as American author Victor LaVelle - and others - say to camera in talking-head clips throughout the exhibition: you are much more likely to get people to consider difficult topics in a fantasy world than you are if you present them in reality.

This is true of games too, I think. I often wonder what effect morality has had on our minds because of the games we've played. Am I kinder and more aware because I've had to solve so many ethical dilemmas in role-playing games over the years? Naturally! Although, didn't I solve a lot of them with violence? Oops! Bad example Bertie, move on. But speaking of games, something else I worried about, going into the exhibition, was gate-keeping. I worried the British Library might suggest the only acceptable fantasies were the ones it displayed, and that those would be old and stuffy. But fair play to the curators because it didn't.

Granted, there is an emphasis on books because the British Library has an incredible collection to pull from, and it would be silly not to. Clearly books are the stars. But they're not all that's here. There are games; and I don't just mean one token game, I mean many games. There are the more obvious inclusions like Dungeons & Dragons and Warhammer and The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim, but there are also others like Planescape: Torment, which I didn't expect, and Fallen London. There's a huge projection of Dark Souls 3 on one wall, which I'm sure will earn the library serious brownie points. There's even a corner devoted to LARP and fan-fiction, and a wall of Magic: The Gathering cards.

Comics are given space - I spotted a Wicked + The Divine book I own at one point, and felt very pleased with my taste in things - and Neil Gaiman features heavily, as well he should. There's a display for the Welcome to Night Vale podcast, in addition to the obvious nods to TV and film. And the feeling this all gives me is encapsulated perfectly when I hear a couple - looking at costumes from the original Dark Crystal film - talking about how they think the recent Netflix Dark Crystal series was underrated, because I do too! I almost blunder into their conversation in loud agreement, but decide against it because this is a library after all. But I feel very seen. I feel like I belong. And seeing the things I like here, next to things like Homer's Iliad and Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings - legendary things - feels very validating.

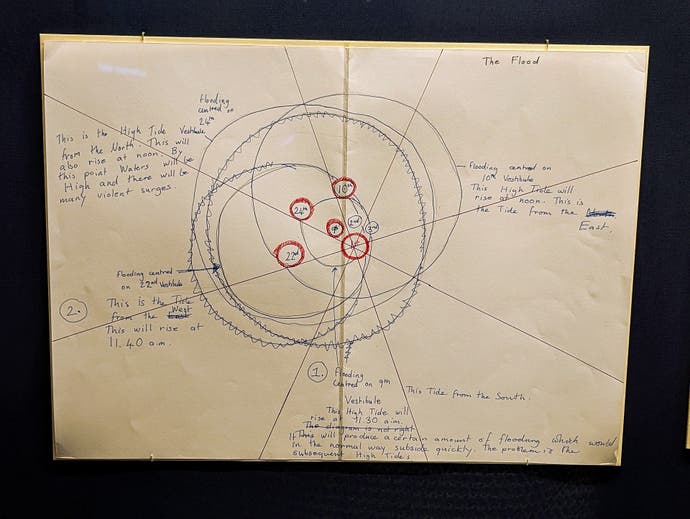

The other thing I find really fascinating about the exhibition is the notebooks of authors that are on display, and all the crossings-out and scribbles and sketches in them. There's one sheet of paper on which Susannah Clarke, the author of Piranesi - a book I really love - tried to sketch the movement of the tides and how they would flow. And it's just a scribble of a circle, really, gone around a few times, with some spindly arrows pointing here and there and a few words accompanying them. It's totally unremarkable, if you don't know what you're looking at. But if you do know what you're looking at, and you know the final story, it's a captivating insight into someone's creative process.

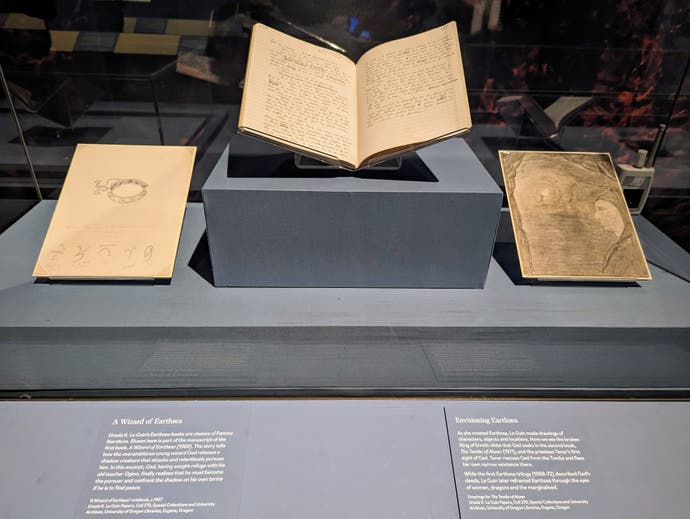

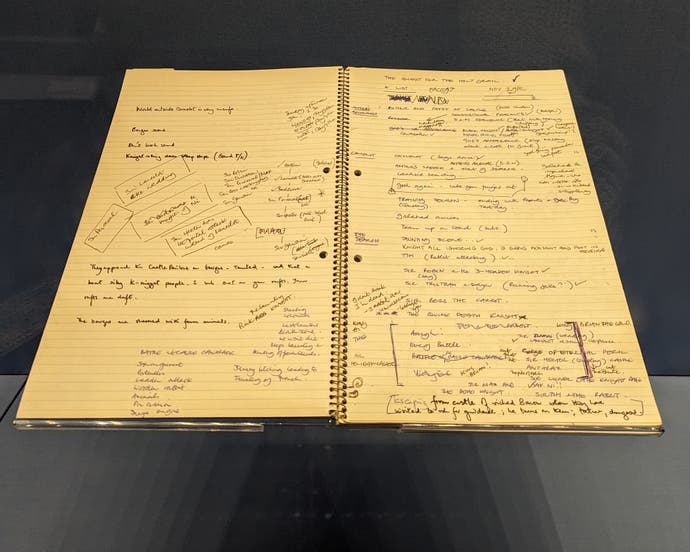

It's similar to seeing the notebook of Ursula le Guin where she laid down the story for A Wizard of Earthsea, which is an all-time great and which shaped me and my fantasy taste. I've got a shadowy monster tattooed on my arm in partial reference to it. But this notebook is again, totally unremarkable - it could be one of mine. And that makes it so much more approachable. In it I see le Guin forming an idea, quizzing herself and honing, honing. It's tremendously humanising. And look over there: it's a very scruffy script for Monty Python and the Holy Grail (right next to Thomas Mallory's Le Morte d'Arthur, as it happens - imagine what he'd have thought of that). And I do mean scruffy - I don't know they deciphered it. But this is imagination slapped down on paper as it erupts. I'm glimpsing the rough formation of stars.

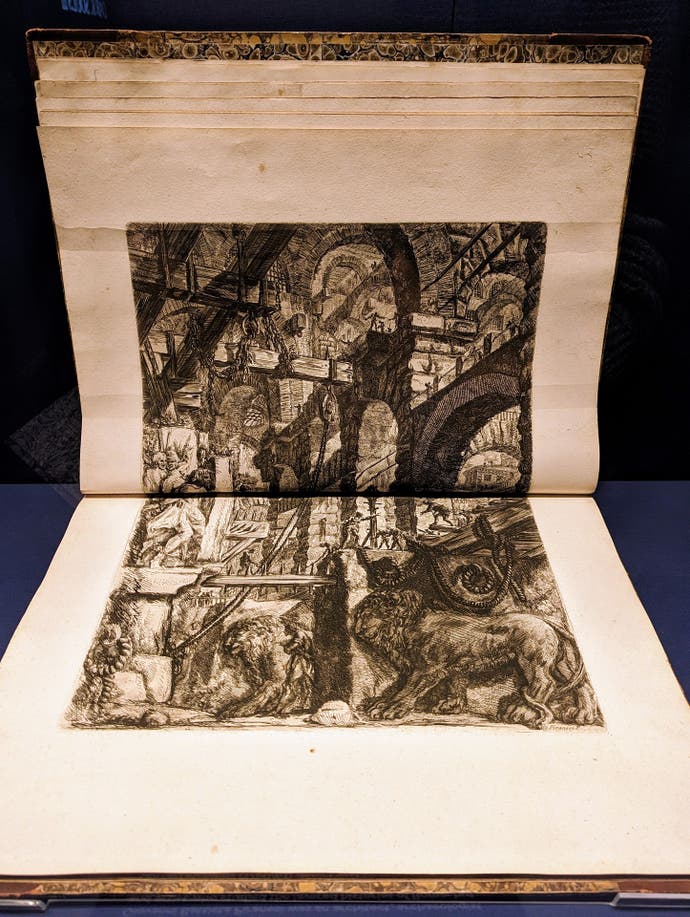

Everywhere I turn in Fantasy: Realms of the Imagination, I see more parts of something that has become a part of me. It's also fascinating to have it laid out before me so I can connect the dots of inspiration from one thing to another. Take Susannah Clarke's Piranesi, for example: it's right next to the actual Piranesi's huge sketchbook of fantastical architecture. So that's where her idea came from. Or take Reverend Rob Kirk's The Secret Commonwealth I mentioned earlier on: that title is the same one Phillip Pullman used for one of his Books of Dust. It must be what he was inspired by. These little revelations fizz and pop as I turn every corner of the exhibition.

It's not massive, the exhibition - I think there's probably an hour or two's worth here, depending on how much you dawdle, plus whatever extra time you spend restraining yourself in the really rather tempting shop afterwards. But then I don't think it was ever designed to include everything, because how could it? And how could you decide - if you were being exhaustive - what would make the cut and what wouldn't? This exhibition is a broad look at the role fantasy has played - and plays - in the world we live in, and the kinds of stories we tell. And what I like about it - what I love about it - is how it suggests fantasy is everywhere and for everyone. Perhaps I will no longer keep my love of it to myself.

Fantasy: Realms of the Imagination runs until 25th February 2024. Tickets are £16. The British Library website is still down - it suffered a cyber attack a few weeks ago and hasn't returned - but you can book tickets here. Note that card machines aren't working in the British Library, so if you want to buy things from the shop, you may need to grab some cash from St Pancras station over the road.