Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story review - classic games, now with fascinating context

Synth you asked.

The black screen has a single white dot at its centre. The expectation is that we're in for something like Pong: something simple, direct, immediate and, as far as games are concerned, ancient.

But then the dot moves, and in its wake we get eruptions of light. Blocks of colour fan out, moving from pink to purple to cyan. The light creates shapes, but what are these shapes? Starbursts, nebula, volcanic eruptions. The screen seems to mirror the action, double it, so we get a lot of crabs with two pincers raised to the sky, a lot of mermaids with two fins, a lot of Rorschach blots. Maybe that's it. You look at these dancing lights, these ripples of colour, all caused by the single white dot, and you see what you want to see.

This is Psychedelia, from 1984. It was the first of designer Jeff Minter's light synths, inspired by the colours and shapes he'd see when he lay around in his room, listening to "the Floyd". I always knew Minter made light synths, because his later games, like Space Giraffe, are often set inside them. But coming across Psychedelia mid-way through Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, I got to appreciate them in a new way.

That shift, from the arcade games he had made prior to this, to something like Psychedlia? Well, 'shift' is the wrong word, for starters. Leap won't do it either. It's like teleportation. He was doing one thing, and now here he is all of a sudden doing something else. The end result is impossible to describe without a certain degree of mutual exclusivity. Psychedelia feels unprecedented, but then you look back at what came before and there's a sudden sense of recognition too. Oh, of course he did this.

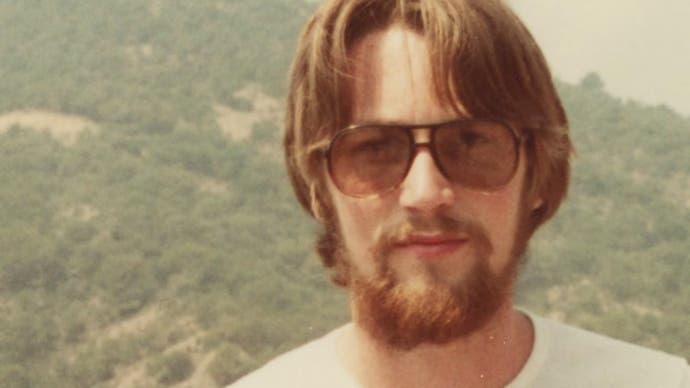

The Jeff Minter Story sees gaming's great digital Romantic given the Gold Master treatment. This series, still thrillingly new, is Digital Eclipse's latest take on game preservation. You don't just get the games, you get the story behind them, unfolding across interactive timelines that include photographs, scraps of testimony and design sketches, alongside delicious playable versions of classics in various stages of development. It's a museum, or a temple to games, and it's the ideal way to see an old game alongside something you rarely get: context.

And the context shifts from one volume to the next. The most recent Gold Master collection looked at Karateka, the forerunner to Prince of Persia. Karateka's story unfolded in a manner that, I now realise, provided an insight into its creator. Jordan Mechner was methodical in his brilliance, in love with details and small, careful shifts from one thing to the next. This was the story of his breakthrough game, and it was also the story of a man who saved every scrap of his work, who was his own biographer, his own archivist.

Minter is so incredibly different. Here, you get a story told through game after game after game, all different in some fundamental way, all fizzing with colour and energy and a very British sense of absurd humour. Minter's games, I now see, have themes they share, but they also move forward in weird lurching leaps of imagination. It reminds me a little of the effect you get from reading a Philip K. Dick story omnibus. You see the master returning to a theme, but changing the variables to make something distinct each time.

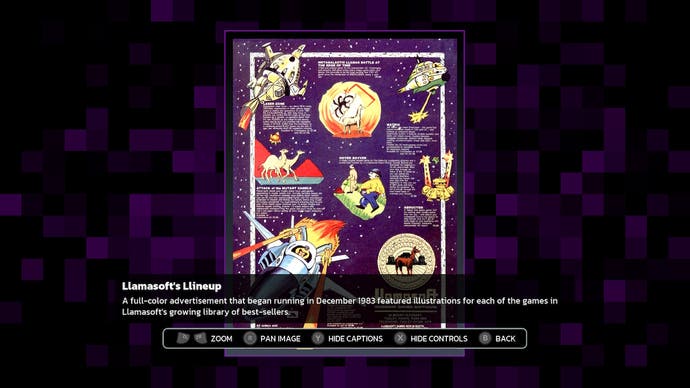

When this is arcade games we're talking about, the rewards are immediate. This is an incredibly generous collection, and while it knocks things on the head around Tempest 2000 in 1994 (granted. it then warps forward for Gridrunner Remastered, a gloriously spacey blaster made last year, to cap things off), all of the stuff you associate with Llamasoft's 80s and 90s heritage is here. Loads of Mutant Camels, lots of Gridrunner - that game appears like an epiphany; you can feel the sense of revelation for Minter - and a very welcome inclusion of Llamatron: 2112, which will certainly be my most played game of the bunch.

I say that, but actually, the stars here for me have been the Minter games I had never played before or - whisper it - had never really heard of. Psychedelia is a thing I struggle to pull myself away from now. It's not the only light synth on here, but it's my favourite. I have fallen into this game over the last few days and I refuse to come out. I may even put on The Floyd myself.

Then there's Laser Zone. 1983. I like the Vic-20 version personally. It's a blaster in which you move a turret around while aliens flock and scatter, but this is Minter, so you move two turrets, one up and down, the other left and right. It's wild. I adore it. I didn't know about it, and yet it could have been released yesterday. It's fresh! Ditto the sort-of-sequel Hellgate in which - of course - you now move four turrets. 1984, that one.

All the games are presented beautifully, with control guides, loads of additional information, and swift loading. But this is not just a games collection. It really is a story, the story of a brilliant man who made brilliant games. It tells you where he came from: Tadley, a town known for making brooms that was also home to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment, where Minter's dad worked. "It was never entirely quiet in our town, even in the dead of night," Minter explains. "The AWRE emitted a steady background industrial rumble at all times, and you could lie in bed at night and listen to the ticking of the criticality alarms guarding the reactors." I always knew Minter's imagination was shaped by games like Robotron and Tempest. But how about this?

And while you don't get any of Llamasoft's recent games, the collection ends with a lovely video piece about Minter and his partner and co-developer Ivan "Giles" Zorzin. It also ends with a lot of people admitting that the brilliant, terrifying, gorgeous thing about Llamasoft is that their games continue to get better and better and better, Space Giraffe! Polybius! Akka-Arrh! All of these make me think that, if we ever get it, Llamasoft 2: The Rest of the Jeff Minter Story is going to be unmissable.

A copy of Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story was provided for review by Digital Eclipse.