Kingdom Come: Deliverance review - history is a double-edged sword

Back to the Dark Ages.

Kingdom Come: Deliverance and the history it explores are inseparable. There hasn't been a medieval world this real and substantial since The Witcher 3. The sense of time and place it conjures is astonishing. You feel your feet squelching in muddy, rutted paths, and smell the manure on the fields around you. But what you see isn't a fantasy world reinforced by a culture's past: it is a culture's past - its bones are made out of it. Kingdom Come is the most believable adventure into medieval history I've ever experienced.

That's the hook: realism. This is the dungeons-and-no-dragons role-playing game sprung from Kickstarter into a full-sized multiplatform release. The RPG offering a first-person medieval simulation like an Elder Scrolls game, with a world living around you, but without the fantasy, magic and monsters. Instead, it's developer Warhorse's own Czech history brought to life from the year of 1403, and the detail with which it has been recreated is staggering.

Kingdom Come hasn't tried to condense a whole world into a game, but instead focused in on a 16 square kilometre area of rural Bohemia, and the dozen or so small villages and towns found there at the time. Nothing feels made up. Everything is placed with the certainty of historical reality behind it; shops are where they are because it made sense at the time - bakers here, weaponsmiths and blacksmiths there. Inns emerge naturally as the town's beating heart - the first port of call for a traveller who can buy lodgings for a week at a time, as I suppose you once would. Everywhere there are windows like this into the past.

Between the settlements is the tranquility of the countryside, birds trilling and flowers gently swaying. In the forests there's the hushed atmosphere a leafed roof brings, as deers scarper and hares and rabbits startle. And at night, wolves howl. This is a living world, made of rain and sunshine and even bone-shaking thunderstorms.

The meticulous eye for detail spreads into the game's systems, the standout being the most realistic recreation of sword fighting I've seen in a game. Swords and fighters are physical objects clad in all sorts of physical armour objects which react in unique ways. One cannot simply slice a plated opponent like a ham.

Combat revolves around attacking and defending areas governed by a kind of directional wheel. Stamina stops you going all out, and if you're hit while breathless you take lasting damage. You also see your viewpoint spin when someone lands a meaty blow, mimicking the disorientation you feel for real when someone smacks you.

When it works, it's a martial dance of careful timing and study as you watch an opponent to see where their guard leaves them vulnerable. You can feint, string together combos and respond with counters. There's genuine depth and skill to it. But when it doesn't work, it's infuriating. Trying to perform combos using a mouse, which slides too easily between attack areas, can feel like an impossibility (it does work better with a thumbstick), and trying to manage multiple opponents with a sluggish lock-on ends in death more often than not.

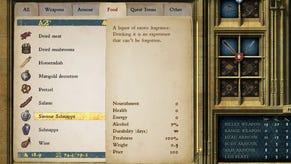

Underneath Kingdom Come's many systems are skill lines - you improve your skills by using them, as in an Elder Scrolls game - and there are perks to unlock in most of them. There are the obvious combat skill lines with their combos and damage boosts and defense bonuses, and stealth lines with backstabs and lockpicking. And there are more quirky skills like drinking and reading too. There are skills galore. And everything is collated in a wonderful set of ornate menus. The maps! Oh, you should see the maps.

There's a clothing and armour system with more layers than an onion. My hero has a plate chest piece over a chainmail shirt over a linen shirt, a scaled cap over a mail hat over a padded hat, banded trousers over mail trousers, then boots, gloves and arm vambraces. Each piece complements another by, say, padding blows from blunt weapons. It's depth under depth and historical explanations everywhere you look. It's armour based on an understanding of combat rather than an appreciation of aesthetics.

Kingdom Come is shaped and spurred to life by a surprisingly entertaining story about a boy called Henry, who finds himself unexpectedly thrust into a lord's service and into climbing the ranks of feudal society. There's a sense of B-movie-ism compared with a blockbuster like The Witcher 3. The quality across the board isn't as uniformly high: the characters don't look great, the animations aren't that smooth, and the voice acting varies wildly. But Kingdom Come isn't bad. The directed cinematics can often deliver surprising naturalism, and I really warmed to actor Tom McKay's affable portrayal of Henry after a while. There are some memorable moments - some touching, others very funny. There's a playfulness and irreverence underneath all the history.

The story also helps drag Kingdom Come out of the mud it can sometimes get bogged down in. I appreciate Warhorse's efforts to make quests a bit trickier than going from A to B, but satisfying C, D and E every time can get tiring. On top of this is a constant need to manage your inventory after every fight, to shift the heavy gear to your horse before shifting it back again before you sell. It sounds like a little detail, but in the flow of the game it's a niggling constant and adds up. That's on top of repairs to carry out, food to find and beds to sleep in, both to keep energy up and to save your game - the only way to save on the fly is via a Saviour potion.

In other words, you don't get anywhere quickly in Kingdom Come, which is fine when everything is going well but not when you're snagged on another of the game's jagged edges. I managed to freeze a village in an un-progressable state by going somewhere before I ought to, for instance, and it took me a couple of hours to notice and reset. I managed to kill a bastard of a knight before I ought to and stuck the game in a similar state, and again it took me hours to rectify. I've been flagged as a criminal for no apparent reason and slung in jail for days. I've spent hours lost in the woods only to stumble on the area I needed to stand in to trigger a 'quest complete' message. They are kinks which contribute to a general feeling of jankiness across the whole game.

When Kingdom Come does succeed, it's peerless. The Elder Scrolls and The Witcher can feel flimsy next to the sophisticated systems and heft of history on show here.

But there's also a big problem. There are no people of colour in the game beyond people from the Cuman tribe, a Turkic people from the Eurasian Steppe. The question is, should there be? The game's makers say they've done years of research and found no conclusive proof there should be, but a historian I spoke to, who specialises in the area, disagrees.

"We know of African kings in Constantinople on pilgrimage to Spain; we know of black Moors in Spain; we know of extensive travel of Jews from the courts of Cordoba and Damascus; we also know of black people in large cities in Germany," the historian, Sean Miller, tells me. Czech cities Olomouc and Prague were on the famous Silk Road which facilitated the trade of goods all over the world. If you plot a line between them, it runs directly through the area recreated in Kingdom Come. "You just can't know nobody got sick and stayed a longer time," he says. "What if a group of black Africans came through and stayed at an inn and someone got pregnant? Even one night is enough for a pregnancy."

It's not conclusive proof but it's readily available doubt to undermine Warhorse's interpretation. What muddies the water further is whose interpretation it overridingly is: creative director, writer and Warhorse co-founder Daniel Vavra's. He has been a vocal supporter of GamerGate and involved in antagonistic exchanges on Twitter (collected in a ResetEra thread). More recently, he wore the same T-shirt depicting an album cover by the band Burzum every day at Gamescom 2017 - a very visible time for him and his game. Burzum is the work of one man: Varg Vikernes, a convicted murderer and outspoken voice on racial purity and supremacy. He even identified as a Nazi for a while.

This isn't to say Kingdom Come: Deliverance is a hotbed of racism, because it isn't. The Turkic Cumans speak a different language and are a hostile enemy, which seems like a limited portrayal but no less so than any other war game I can think of. Then again, I'm white, so maybe I've missed things. And racism can take many forms, one of them being exclusion.

More apparent to me was the back-slapping laddishness revolving around bedding women. I'm pursuing a love story over here, while over there bedding a noble and having one-night stands. That's in addition to my Troubadour perk which makes me even more irresistible to women and lets me use the "bathwenches" for free, which ties into a key mechanic of keeping yourself clean and patched up. It also means I get the Alpha Male buff (+2 to Charisma) because I've been satisfied and apparently it shows. It literally says that. The game's Codex even feels the need to describe the ideal woman of the time: "a thin, pale woman with long blonde hair, small rounded breasts, relatively narrow hips and a narrow waist".

All of which means that a shadow lingers over Kingdom Come: Deliverance. Instead of challenging the Dark Age it reinterprets 615 years later, the game seems to delight in it. Instead of seeing notes in the margin of a history book, we get what feels like a glossy pamphlet advertising an escape into an oddly romanticised past. And it's that, ultimately, which makes me too uneasy about Warhorse's work to be able to recommend it.