Far Cry's villains are sick of Far Cry

The definition of insanity.

Beware serious spoilers for every numbered Far Cry game except the first. You have been warned.

You don't need to actually play Far Cry 5 in order to finish it. All you need do is enter the church after the introductory cinematic, wait for the order to arrest your antagonist, cult leader Joseph Seed, then drop the pad. "God is watching, and he will judge you on what you decide here today," your quarry says, holding out his wrists. The silence lengthens, tension dribbling away into fidgety embarrassment. Finally, another character pushes down Joseph's arms and you walk back to the door. Beyond it, there is only the credits reel. A poor return on £50, I guess, but in a way this is the most uplifting of the game's three endings: it spares you a bloody struggle for control of Hope, Montana that will ultimately prove meaningless when a mushroom cloud sprouts from the horizon. The "Father", it transpires, was right about the end of the world all along. In asking you to leave him alone, he was only trying to save you a bit of time and legwork.

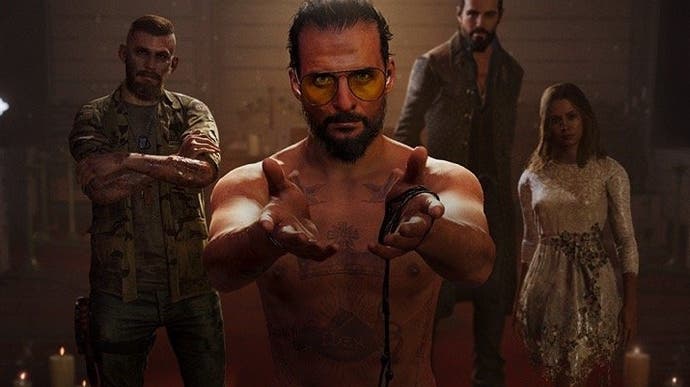

Far Cry 5's apocalyptic ending - the one you'll reach if you assume that plot progression always comes about through aggression - is basically a cop-out, a dog-eared doomsday spectre thrown across the rails of a story that aims to interrogate a violent society, but is largely content just to echo that violence as part of yet another exercise in colonising a map screen. It is, however, intriguing for how it retrospectively robs every player action of sense or significance - and for how Joseph Seed, like every Far Cry villain before him if rather more explicitly, knows this revelation is coming from the outset. Arrest the Father as ordered, and you'll find that the ensuing mayhem is peppered with scenarios that feel like self-commentary, a meditation on the callousness and futility of playing Far Cry 5 as it was designed to be played.

There are, for instance, the hallucinatory rampages you're put through by the social Darwinist and veteran Jacob Seed, repeat runs of a timed assault course made up of familiar locations with ally characters as enemies. Though based on accounts of hypnotism in real-life cults, these pressure-cooker levels feel like a designer's critique of the bloodshed that already characterises Far Cry, the fluid chaining of takedowns, slides, headshots and weapon swaps that should, by this point in the proceedings, be second nature to the player. It's as much a nod to the tabloid stereotype of the videogame "massacre simulator" as it is cultish mind control, and such moments of self-awareness occasionally verge on actual self-reproach. "When are you going to learn that not every problem can be solved with a bullet?" the Father will snap at you, many shoot-outs later, the immediate counter being that Far Cry has never been all that interested in problems that can't be solved with bullets.

Shame about its own love affair with colonial violence is as much Far Cry's calling card as radio masts and self-propagating fire. Joseph Seed is the latest in a series of antagonists who serve as guilt-ridden author proxies, all to some extent conscious of their place in the series' endless, torrid saga of destruction and conquest, all inviting you to wash your hands of the carnage even as they strive to take you apart. The root of this strange meta-tragedy is Far Cry 2, where the designer Clint Hocking's dream of a solution to the problem of "ludonarrative dissonance" is checked by a rather staggering degree of fatalism. Released a decade ago, Far Cry 2 was billed as a game of free, meaningful agency versus the glossy narrative constraints of a Call of Duty 4, the first "true" open world FPS, made up of dynamically entwined systems that allow players to "author" their own experiences, and major characters who can die at your hands without impeding the wider plot. Its contemporary African setting also, however, takes inspiration from Joseph Conrad's novel Heart of Darkness and its film adaptation, Apocalypse Now. This leads to something of a spiritual conflict, because where Hocking and his team are keen to impress that choices have real consequences, Conrad's book is broadly about the futility of action in a world that is broken beyond repair.

As the critic (and Ubisoft marketing man) Jorge Albor writes, the game "depicts, and perhaps validates, prominent perceptions of Africa as a carrier of disease, of contagion, of civilisation spoiled. Politically and culturally, many see Africa as an automaton, a golem created by colonialism, abandoned and doomed to carry out its wicked fate, becoming a perpetual maelstrom of violence and instability." Much of this is expressed to the player by the Jackal, the American arms dealer you're dispatched to assassinate. The Jackal comes across at first as cheerily black-hearted, selling weapons to both sides of the region's civil war and sneering at the supposed moral authority of the West, but as you push deeper into the narrative and uncover tapes of his conversations with a journalist, you'll detect a growing despair. "There's no ideology at all," he marvels at one point. "There isn't even a desire to win. There's no sense in it, no sense in it at all. What would it matter if we butchered the lot of them?"

This despair infects and corrodes the moment-to-moment of the game in a way that is startling to revisit, given the morbid slickness that has become typical of Ubisoft's shooters. Far Cry 2 is grating and intractable where its successors are disorderly yet stylish, with old, rusty firearms (many, as the Jackal recalls, decades-old relics of wars elsewhere) jamming when least convenient and wildfires quickly suffusing dense canyon environments, engulfing player and opponent alike. Outbreaks of malarial fever wrest control away without warning, fast travel points are relatively scarce, and checkpoints repopulate themselves with guards between visits, denying you the warm glow of ever-expanding dominion that has become the open worlder's stock in trade.

To attempt to rescue this land from the Jackal, assuming that is indeed your aim, is inevitably to add to its chaos, a knowledge that leads your adversary to propose a joint suicide as the only way of achieving some kind of closure. "Every cell of this cancer has to be destroyed," he tells you. "That includes you and me. If we don't finish this then the whole mission has been a waste, a farce. It'll start up again like it always does." The Far Cry series is, in that regard, your and the Jackal's failure: the scenery may change from game to game, and the tools of destruction may have become shinier and more reliable, but that postcolonial maelstrom remains.

In keeping with bad boy nihilists everywhere, the Jackal is a fan of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. During your first meeting, as you lie sickening on a hotel bed, he quotes the latter's theory of a "will to power" at you, declaring that any living being "seeks above all else to discharge its strength". Another of Nietzsche's ideas seems relevant here, that of eternal recurrence. In brief, since there is a finite amount of matter and energy in the universe, the universe can only ever assume a finite number of states, repeating those states endlessly. I doubt Nietzsche would be pleased by the association, but it makes a nice gloss for a sandbox shooter that prides itself on freedom of choice but always, somehow, defaults to conquering a map by busting fortresses and unlocking spawn points. There are, moreover, plentiful allusions to the dilemma of recurrence in Far Cry 3's writing.

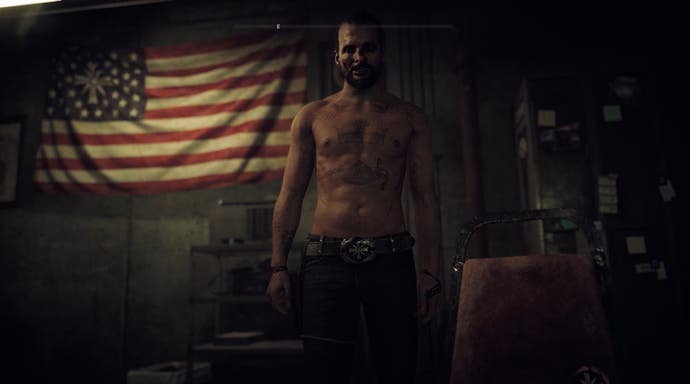

In particular, the pirate warlord Vaas is haunted by the possibility that all of this has happened many times before. As he puts it in a now-infamous speech, "insanity is doing the exact same fucking thing over and over again, expecting shit to change". This reflects Vaas's mounting derangement at repeatedly failing to kill player character Jason Brody, but the invocation of eternal recurrence also speaks to how Jason is, in a way, his double. Both are groomed as mythical alpha warriors by Vaas's sister Citra - a stereotypical sexy tribeswoman who has attracted plenty of derision - and both are ultimately called upon to choose between their loved ones and the monsters they've become.

As with the Jackal and Joseph Seed, Vaas is to some degree an interrogation of the player's role in the world and of Far Cry's supporting structures, though he is of course powerless to do anything about them. The game's writer Jeffrey Yohalem has (defensively) styled the game a critique of Far Cry and its genre, an "exaggeration" of tropes such as the noble white saviour. This emphasis on self-scrutiny charges another Vaas line with peculiar force. Having offered his thoughts on insanity, he abruptly flies into a rage, yelling "I'm sorry, but I don't like the way you are looking at me" in a curious reminder of the first time you meet him, when he screams at Jason's older brother Grant for not looking at him.

It's hard to know what to make of his fury, given that you can't see Jason's expression, but it's possible that the line exists to get you thinking about the distance between character and player, keeping you at a remove even as the game's animations do their utmost to make you feel like Jason's body is your own. Another, reachier interpretation is that Vaas objects to being looked at because in a game like Far Cry, looking at things is fundamentally obscene: not just the prelude to a gunshot, but a way of marking people for destruction, objectifying them. Part of Far Cry's undeniable success as a sandbox game is its a tagging system, whereby you use a scoped device to highlight enemies on your HUD, making them easier to predict and avoid, easier to perceive as mere moving parts and harder to regard as fellow living beings.

Where Joseph Seed reacts to the futility of Far Cry's on-going war with righteous sorrow, the Jackal with grim horror and Vaas with a train of expletives, Far Cry 4's dapper tyrant Pagan Min is alone in seeing the funny side. Clearly modelled on Batman: Arkham Asylum's Joker, he serves less as a nemesis than a whimsical audience, right up to the point when you scale his mountain lair and put a gun to his head. It's at this stage that Min springs his trump card: had you only resisted the urge to run out into the open world and start "throwing your shit around", he chortles, you could have carried out your ostensible goal in the game within the first 20 minutes.

Player character Ajay Ghale travels to Far Cry 4's fictitious Kyrat to inter his mother's ashes. Min, who is actually the father of your half-sister, flies out to meet Ghale at the border, only for the situation to explode following the discovery of resistance fighters in the back of the bus. The subsequent scenes are a small masterclass in testing the extent to which you are already a slave to Far Cry's formula, whether you are capable of registering hints about alternative outcomes. After spiriting you off to his palace, and sending a companion of yours to the torture chamber, Min asks you to wait for him at the dinner table while he takes a call.

If you're already dancing to Far Cry's beat, you'll take this as your cue to escape the palace and kick off 30-odd hours of outpost-flipping and tower-climbing. If, however, you resist the tug of the combat sandbox - perhaps bearing in mind the game's choice of title track, "Should I stay or should I go" by The Clash - Min will eventually return and help you spread your mother's ashes before handing over the keys to his kingdom. You might, of course, have misgivings about buddying up with a sadistic despot, but the alternatives aren't much better. Aiding the resistance results in either a brutal theocracy or an authoritarian state fuelled by the drug trade and child labour. As with Far Cry 2's Africa, Kyrat is a terminally diseased realm, a place where ideologies collapse into empty slaughter, and if Min is alive to the joke, he is still part of the punchline.

Which brings us back to Far Cry 5. The story's other twist, should you choose to resist Joseph Seed at every turn, is that the end of the world isn't the end of the world. The nuclear blast leaves everybody in Hope, Montana dead save the Father and yourself. Rather than killing you, he drags you to a prepper bunker, ties you up and declares you to be his only living family. So the story stumbles to a halt, with protagonist and antagonist staring at each other glassily in the bleeding, smoking wreckage of yet another irredeemable landscape. Will Far Cry ever transcend the things it feels guilty about? It's difficult to see how. As the Jackal might comment, musing on the Stone Age spin-off Far Cry Primal: "That's how it works. It worked that way a million years before there were men saying otherwise. That's probably how it should work."